By Antonia Dimou

Published at National Security and the Future Journal, Vol. 18, No 1-2, 2017

Introduction

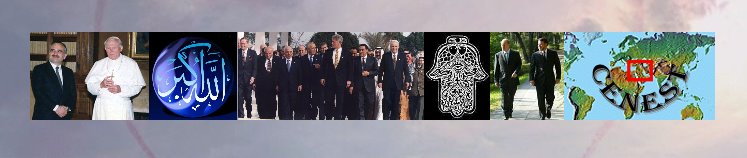

The East Mediterranean’s gas resources can promote cooperation, resolve conflicts and deliver financial benefits contributing to the economic development of Israel, Greece and Cyprus, advance the energy security of Jordan and Turkey, and present new prospects for Lebanon, Syria and the Palestinians.

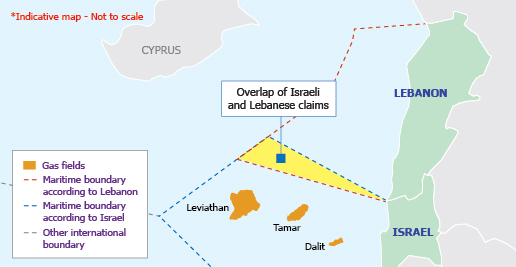

Figure 1: The main gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean sea

ISRAEL: Untying the Gordian Knot of Natural Gas

The approval of a revised framework for gas regulation by the Israeli government eight years after the discovery of offshore gas in Israel resolved the antitrust stalemate but has done little to address other challenges that delay the development of Israeli gas fields such as high risks for potential buyers and uncertainly over export markets.  Despite the approval by the Israeli government of natural gas exports to Egypt, the deal signed between Israeli Tamar gas field’s partners and the Egyptian Dolphinus Holdings for the latter to purchase $1.2 billion of gas for a minimum of 5 billion cubic meters (cbm) in the first three years , has not yet materialized. Israel is deprived of an outlet for its gas through the Egyptian under-used LNG export facilities in Idku operated by BG Group and Damietta by Union Fenosa Gas to process Israeli gas to Europe and other lucrative markets in Asia.

Despite the approval by the Israeli government of natural gas exports to Egypt, the deal signed between Israeli Tamar gas field’s partners and the Egyptian Dolphinus Holdings for the latter to purchase $1.2 billion of gas for a minimum of 5 billion cubic meters (cbm) in the first three years , has not yet materialized. Israel is deprived of an outlet for its gas through the Egyptian under-used LNG export facilities in Idku operated by BG Group and Damietta by Union Fenosa Gas to process Israeli gas to Europe and other lucrative markets in Asia.

Despite the approval by the Israeli government of natural gas exports to Egypt, the deal signed between Israeli Tamar gas field’s partners and the Egyptian Dolphinus Holdings for the latter to purchase $1.2 billion of gas for a minimum of 5 billion cubic meters (cbm) in the first three years , has not yet materialized. Israel is deprived of an outlet for its gas through the Egyptian under-used LNG export facilities in Idku operated by BG Group and Damietta by Union Fenosa Gas to process Israeli gas to Europe and other lucrative markets in Asia.

Despite the approval by the Israeli government of natural gas exports to Egypt, the deal signed between Israeli Tamar gas field’s partners and the Egyptian Dolphinus Holdings for the latter to purchase $1.2 billion of gas for a minimum of 5 billion cubic meters (cbm) in the first three years , has not yet materialized. Israel is deprived of an outlet for its gas through the Egyptian under-used LNG export facilities in Idku operated by BG Group and Damietta by Union Fenosa Gas to process Israeli gas to Europe and other lucrative markets in Asia.

The only secured export agreement is the Gas Sales and Purchase Agreement (GSPA) signed between Noble Energy Inc and Jordan’s National Electric Power Corporation (NEPCO) for the supply from the Leviathan gas field of approximately 1.6 trillion cubic feet (tcf) over a 15-year period for electricity production .

Out of all export options, the construction of a pipeline that connects Israeli Leviathan gas field to the Turkish coast remains financially attractive despite Israeli reservations over the likelihood of tying its gas into a single market where there is considerable competition. For the gas pipeline project to proceed, it has to overcome the longstanding Cyprus conflict as the pipeline requires crossing Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The Leviathan gas field’s development whose 9 bcm gas surplus is destined for export is to be carried out in two stages: the first lies in four development wells and an annual capacity production of 12 billion cubic meters (Bcm), and the second stage lies in four additional wells and an increase of the capacity production by another 9 bcm. Nevertheless, uncertainly prevails over progress on the basis that even secured GSPAs to supply gas from the Leviathan field to domestic buyers such as IPM Beer Tuvia Ltd are subject to regulatory approval .

Israel’s energy policies should focus on the strengthening of relations between Tel Aviv and Nicosia in parallel to any Israeli collaboration with Ankaraso that an agreement on joint monetization of export-oriented gas resources is favored; regional energy cooperation through increased energy security, and incentivizing American oil and gas companies to proceed with investment in exploration activities and production commitments in Israel; and, look into multiple gas export options so that Israeli gas is not tied to a single market where changing bilateral relations or geopolitical conditions can affect the sustainability of exports and thus impact negatively the country’s energy wealth..

SYRIA: Redefining The Regional Energy Map’s Centre of Gravity

Geopolitics of energy dominate the crisis in Syria. Foreign powers battle control of natural gas resources and the trade routes that bring energy to consumers. Russia seeks to maintain investments in the energy sector in so-called “Safe Syria,” which is a promising zone of natural gas reserves in the territorial waters off Syria’s Mediterranean coast. The significance that Russia attributes to joining the Eastern Mediterranean energy game is underlined by the fact that energy giant Gazprom has reportedly taken over the gas exploration and drilling rights off the Syrian coast from Russian state-controlled Soyuzneftegaz, which in 2014 signed a 25-year agreement with the Syrian government that concedes exclusive exploration rights in Syria’s EEZ .

Syria contains a number of gas fields that have been periodically seized since 2014 by the Islamic State, principally in Palmyra, a city that serves as transit for pipelines carrying gas from fields in Hasakah and Deir Ezzor provinces in northeastern and eastern Syria respectively . ISIS focus around the area of Palmyra is attributed to the fact that the city is the hub between the transfer of the entire Syrian gas production and the power plants that supply electricity and gas to most parts of Syria. The regime’s control of Shaer field (the largest field northwest of Palmyra that feeds the national grid) is considered significant because it impedes the Islamic State from amassing further disproportionate rewards compared to its limited investment of combat manpower.

But as ISIS territory shrinks it seeks to substitute traditional sources of revenue like transit tolls and wage taxes with financial profits deriving from the sale of oil and gas. Upon this strategy, the terrorist organization allegedly sells energy to the Syrian government to power the capital of Damascus and other parts of the country.

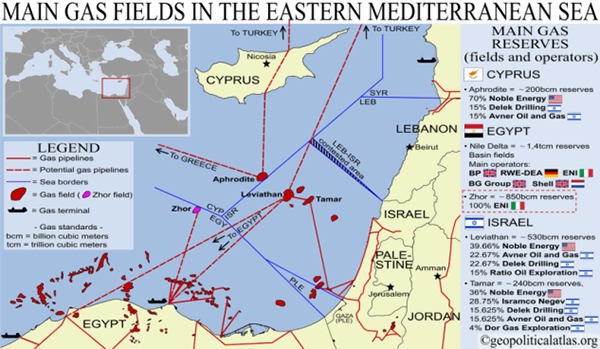

Figure 2: Transition route

Qatar’s energy agenda in Syria needs to be highlighted as it includes a pipeline that would connect Qatar and Turkey through Syria, in order to join the Nabucco pipeline and ultimately reach Europe. For its part, Iran’s energy strategy in Syria centers on the Iran-Iraq-Syria Islamic pipeline project, originally signed in 2011. The project is intended to transport Iranian gas through the Gulf to Iraq, then to Syrian and Lebanese ports, with Europe as the final destination.

Notably, Russia’s decision to enter the Syrian conflict has an aspect linked to the control of the country’s energy supply routes. It is acknowledged by regional energy experts that the eight Russian military bases which have been developed over the last year across Syria are along the oil and gas routes with most prominent the base of Tartus where Syria’s prime export terminal is located. Equally important, Russia favors the Shia pipeline that would carry oil from Iran through Iraq into Syria over the Sunni pipeline that would carry oil from Qatar to Turkey via Syria.

The international community’s policies should focus on the resolution of the Syrian conflict as a prerequisite for the development of the country’s untapped offshore gas resources and for attracting foreign investment in the context of a regional energy cooperation setting.

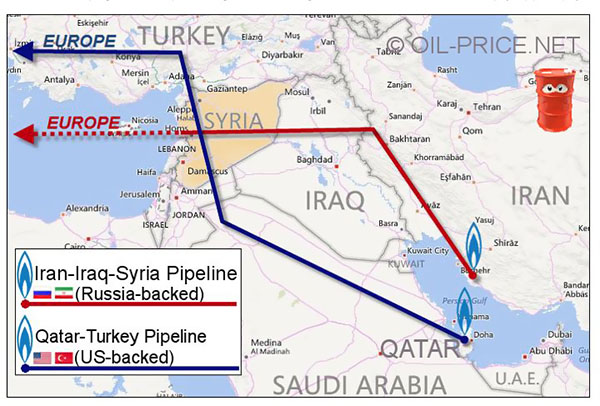

Cyprus in Need Not to Mistake Energy Activity with Achievement

Provided the existence of commercially viable hydrocarbon resources, Cyprus is assessed to get significant economic benefits in the form of job creation, foreign direct investment as well as royalties and taxes paid to the state treasury by energy suppliers. The island’s recent third licensing round for the blocks 6, 8 and 10 within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) has attracted international energy majors such as ENI, Total, Exxon Mobil and Qatar Petroleum on the basis of closeness to the Egyptian Zohr and the Israeli Leviathan gas fields . The rationale is to connect gas discoveries in Cyprus with Egypt’s by pipeline and re-export reserves as liquefied natural gas by utilizing the Egyptian Idku and Damietta LNG facilities. Evidently, the development of Cypriot gas fields necessitates synergies among local and international players, users and producers, eager to export gas to a broader market.

The criteria for the evaluation of the third licensing round’s applications have lied in the technical and financial ability of the energy companies; the financial proposal of the applicant to obtain a license; applicant’s commitment to training of personnel; political considerations in having energy majors involved in the Cypriot blocks; and, any irregularities and lack of responsibility that the applicant may have demonstrated under a previous license in Cyprus or in any other country.

No doubt that a comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus problem should be fortified by the implementation of concrete confidence building measures (CBMs) such as Track-II diplomacy between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots on the future use of the East Mediterranean natural gas resources. All this despite the conventional practice which says that the connection between politics and the development of hydrocarbons should be limited.

Policies should focus on the resolution of the Cyprus conflict as prerequisite for cooperation over East Mediterranean gas production; the creation of an East Mediterranean Energy Cooperation Council (EMECC) that will support the regional energy industry. Members should include governments, energy companies and service providers. The council will serve as a clearinghouse for ideas and plans for mutually beneficial energy developments in the region; and, support of the joint monetization of Cypriot and Egyptian gas resources on the basis that economies of scale reinforce profitability and produce higher government revenues.

Figure 3: Offshore Exploration Licenses Republic of Cyprus

GREECE: Pivotal to Regional Gas Development

Greece has been pivotal to the development of Israel’s natural gas with the acquisition of the Tanin and Karish fields by facilitating competition in the Israeli market in accordance with the revised Israeli regulatory framework. Greek private E&P company Energean Oil and Gas currently owns 100% and is the Operator of the two Israeli gas fields considered as a world class asset with 2,4 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas, contingent reserves, and more than 20 million barrels of light oil, contingent and perspective reserves.

Israel has facilitated Greek energy interests, which can help Europe diversify supply of energy resources. Energean’s ability to present a reliable Field Development Plan (FDP) for both fields so that first gas is produced in 2020 looks promising. The company has emerged as a smart investor given it managed to acquire two new licenses in Israel and another two in Western Greece during the low part of the cycle of the upstream industry; it also has a powerful shareholder basis such as ship owners, petroleum engineers, former officials from the financial sector, and the US based fund Third Point; a long term off take agreement with BP; and, the company is backed by financial institutions like the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development.

Pursuant to the overall strategy of Greece in not only penetrating the East Mediterranean energy landscape but also in exploiting and developing its own gas fields in the Ionian Sea and South of Crete, the Greek Ministry of Energy is ready to sign a contract with French Total’s JV with Edison and Hellenic Petroleum for offshore Block 2 located west of the island of Corfu as outcome of the 2014 International Licensing Round .

Figure 4: Areas of Operation

It may nevertheless be risky for Greece to re-launch a new Licensing tender at the current low price levels considering increased exploration costs in deep and ultra-deep waters as well as the fact that Athens political instability dissuaded interest of international energy companies as already evidenced in the 2014 International Licensing Round where no bid occurred for the seventeen out of the twenty offered fields.

PALESTINE: Seeking a Way Out of The Energy Deadlock

The Palestinian Gaza Marine gas field, one of the first regional discoveries back in 2000 remains untapped despite its location close to the shore. The field’s new operator, the Royal Dutch Shell that owns 60%, estimates that its development is impeded by low oil and gas prices . For a breakthrough in the field’s $500 million development, the project’s financial support either by the World Bank’s Partnership for Infrastructure Development Multi-Donor Trust Fund or by American financial institutions like the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) can prove vital. The value of American financial support in the field’s development is two-fold as it can help address Palestinian development challenges and advance U.S. foreign policy priorities.

The exploitation of the Gaza marine gas field would help generate revenues, offer a domestic source for electricity generation and for water desalination, and prioritize export to neighboring counties like Jordan. Already, in implementation of its strategy to diversify energy sources of supply, Jordan has signed a Letter of Intent (LOI) to import 1.5-1.8 bcm per year from the Palestinian field.

Noteworthy, a pessimistic outlook seems to prevail for the development of the Rantis oil project in the West Bank due to high political risks . Only one offer was received that did not even meet the technical or financial conditions of the tender issued in 2014. To ensure the development of the oil project, the Palestinian Authority considers the establishment of a Palestine Investment Fund-led national consortium to attract international operators.

Figure 5: Areas of Operation

LEBANON: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back On Natural Gas

Lebanon’s decision to open a new pre-qualification round for oil and gas companies interested in participating in the first International Round for five offshore blocks marks a breakthrough after three years of political impasse.

The Lebanese government’s approval of a decree stipulating Exploration and Production Agreements (EPA)and another decree on the delimitation of Lebanon’s territorial sea and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) have aimed to pave the way for tendering Lebanon’s offshore area. According to energy experts, both decrees create more problems rather than provide solutions due to lack of transparency that favors avidity and rent-seeking behavior among the various sectarian groups that dominate the political decision-making process.

Figure 6: Overlap of Israeli and Lebanese claims

Despite persistent American diplomatic efforts discouraging Lebanon and Israel from energy exploration in contested waters, Beirut decided to initiate a tender process to award licenses, which Israel considers its own. A bilateral crisis could erupt with Israel if Lebanon proceeds with non-consensual economic activity in the disputed area; thus openness to dialogue between Lebanon and Israel is critical when it comes to the northern limit of Israel’s Territorial Sea and EEZ in accordance with the International Maritime Law.

Challenges that could undermine the development of Lebanon’s gas potential lie in the lack of strong governance. The country’s domestic politics is overwhelmed by constant conflicts over the distribution of political power; the absence of an anti-corruption framework, and lack of free, non-discriminatory competition. Often, weak institutional and administrative frameworks in Lebanon guarantee a gap between declared government plans and ultimate delivery. No doubt that the development of potential discoveries could help Lebanon reduce its domestic energy-deficiency and dependence on oil imports if an exploration, production and monetization model based on best-practice standards and technical expertise materializes.

Policies should focus on the establishment of anti-corruption mechanisms for the Lebanese oil and gas industry, such as the creation of sovereign wealth funds that take part of the gas profits and allocate them to the development of infrastructure projects; and, encouragement of sound institution-building to promote transparency by disclosing to the public all information pertaining to the energy sector including licenses, contracts, and production and revenue data.

Egypt and Turkey Share Common Regional Gas Ambitions

Situated right off of the Egyptian coast, Zohr field is possibly the largest gas field in the world, with an estimated 30 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The development of the Zohr gas field expected to produce 20-30 bcm annually for 20 years will primarily serve the Egyptian domestic market, making up for a rapid decline in production which has left Cairo increasingly struggling to meet its domestic demand . Concurrently, it will free up much needed funds for other sectors of the economy, such as health and education.

The impact of the Zohr gas field could well go beyond Egypt’s boundaries, due to its location and infrastructure given that it is close to Cypriot Aphrodite and Israeli Leviathan gas fields, thus allowing the development of the fields to be coordinated, and the economies of scale needed to put in place a competitive regional gas export infrastructure. Cooperative scenarios foresee gas imports from Cyprus and Israel to Egypt with the aim of being exported as LNG to Europe and Asia; despite domestic controversy, Egyptian companies have conducted talks to import gas from Israel, and the Egyptian government signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Cyprus to import gas from Aphrodite field.

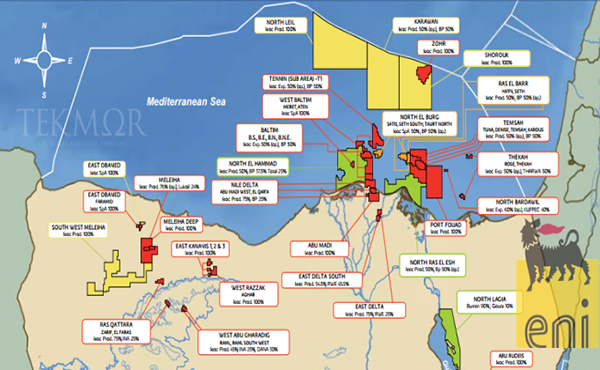

New discoveries guarantee that in the long-term Egypt’s production will reach levels of self-sufficiency; it is in this context that British Petroleum (BP), a heavy foreign investor in Egyptian fields, recently completed a number of transport and processing agreements accelerating the development of the Atoll field which contains an estimated 1.5 trillion cubic feet of gas ; announced the construction of a natural gas processing plant in Rosetta (Rashid) city, with a capacity ranging from 600-700million cubic feet per day; and, publicized the discovery of a new natural gas field in the BaltimSouth Development Lease in the East Nile Delta, 12 kilometres from the shoreline.

Figure 7: Areas of Operation

Additionally, the Suez-Med Pipeline and the Suez Canal’s extension can be viewed as motivators of Egypt’s prioritization of gas production. These projects provide preferential economic zones; special arbitration and policies, such as restoration of corporate funds spent in Research & Development; and provision of government loans in local currency with low interest rates. However, regulatory changes in the rest of the country that could turn Egypt’s gas sector into a must-be place for both suppliers and investors are slow, especially when it comes to regulating gas prices and trading services.

Equally interesting are Turkey’s ambitions to become a major Eurasian energy hub. The concept of creating a regional trading hub in proximity to the East Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Europe with Turkey at the epicentre gains significant ground on the basis of viewing natural gas as a shared economic benefit in the form of transit fees, new refineries and trading facilities. It is estimated that despite the Turkish-Israeli rapprochement, the East Mediterranean gas is trapped given that global low gas prices make less feasible the development of regional fields and the construction of pipelines. At the same time, the presence of cheap Russian gas and the discovery of new resources in Africa and the US make the East Mediterranean gas less attractive. To overcome these hurdles, East Mediterranean gas could be shipped to Turkey viewed by many energy experts as trading hub. Existing gas pipelines in Turkey guarantee the presence of qualified technical labour force capable to maintain and repair energy infrastructure, while its close vicinity to energy producers and consumers makes the country attractive to East Mediterranean neighbours.

Epilogue

Gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean have the potential to transform the energy outlook of individual countries, as well as foster regional energy cooperation. This is a period of disruption with financial upheavals and political instability, hence new opportunities emerge for those who are bold and ready to work. Regional countries need to identify to this group.

References

1. Al Khalidi, S. “Islamic State Militants Capture Palmyra Despite Heavy Russian Strikes”, Reuters, 11th December 2016.

2. BP Steps Forwardwith Atoll Gas Discovery Development, LNG World News, 20th June 2016.

3. Cohen, H. “Israeli Government to Allow Leviathan Gas Sales to Gaza”, Globes (Israel’s Business Arena), 19th March 2016.

4. Cyprus Offers Licenses for Three Offshore Blocks, Offshore (Magazine), 30th December 2016.

5. Dimou, A. (2017). Lebanon and Syria: Stuck between a rock and a hard place on natural gas. Modern Diplomacy.

6. Hellenic Petroleum Bags Exploration Block Offshore Greece, Offshore Energy Today.com,7th December 2016.

7. Mustafa, M. “Palestine’s Oil and Gas Resources: Prospects and Challenges”, Accessed at: http://thisweekinpalestine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Palestine%E2%80%99s-Oil-and-Gas.pdf

8. Noble Energy Executes Leviathan Gas Sales Contract With the National Electric Power Company of Jordan, Press Release by Noble Energy Inc. URL: http://investors.nblenergy.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=990815 (26.9.2016).

9. Noble Energy Receives Plan of Development Approval for Leviathan Field Offshore Israel, Nasdaq. Global NewsWire. 2nd June 2016.

10. Norlen, A., Maddock, K. “Giant Gas Field Discovery in Egypt Likely to Impact Global Gas Markets”, Energy Insights (by McKinsey), September 2015.

11. Report: Energean Picks Floating Solution for Tanin, Karish Fields, Offshore Energy Today.com, 11th January 2017. Also, Energean Group Moves Eastwards. URL: http://www.energean.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Mathios-Rigas-NGW.pdf.

12. Rida, N. “Lebanese Government Passes Two Oil, Gas Decrees”, Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (Daily), 5th January 2017.

13. Shaham, S., Weintraub, S. (2016). Israeli Natural Gas Industry – Where do we go now?, Originally published in Oilfield Technology

14. 2016 East Med Forecast: Geopolitics to Rule Gas Deals, Energy Press (Greek Energy News Portal), 8th January 2016.